EXHIBITIONS

PAULA REGO: THERE AND BACK AGAIN

Curated by Adam Budak & Alistair Hicks

Kestnergesellschaft, Hannover

29 October 2022 -30 January, 2023

Paula Rego’s first museum show in Germany sadly opened just after she died.

Everything leads up to the avenging angel, but a Paula exhibition can never just have a single finale. Next to the angel was The Dance, 1988, which she finished painting in the year after her husband Victor died, she has painted two versions of him dancing. One is not quite sure who he is dancing with, but at least one of them is another woman. On the far left is a larger-than-life woman forced to go dancing on her own. It takes place under a full moon which reflects like a half map of Britain on the water. For all its sadness it is a strangely uplifting Romantic picture …

PAULA REGO: THE STORY OF STORIES

Pera Museum, Istanbul

29 December 2022 -23 April, 2023

This was Paula Rego’s first museum show in Turkey

'Never again will a single story be told as though it's the only one’, wrote John Berger, the author of Ways of Seeing. It is a waste of time to look for a single explanation for any of Paula Rego’s works: the one straight lane approach was the old male way of doing things. There were two beginnings to this Rego show. The first drawing shows Elizabeth whispering to her cousin Mary. She is telling the Virgin she is going to have a baby and the father won’t be Joseph – the advice is to call it the immaculate conception. Well, that is one interpretation.

The other picture here is of a pregnant rabbit, so we are not entering the story right at the beginning. The rabbit is telling her father that she is pregnant. Painted in 1981, thirty years after she announced this news to the father, this picture is part of an explosion of suppressed creativity after a decade of difficult times in the 1970s. Most of her early life was lived in fascist Portugal, behind shutters. As an only child she solicited stories from her father, grandparents and favorite aunt. She was terrorised by a tutor, Dona Violeta. She was well-behaved, did what she was told, but from the age of four she started drawing – here in her pictures she could do anything.

A Presence, 1969

Oil on board

65 x 55 cm

George Claessen: Babel to Abstraction Seventy Years of Art and Poetry

AT THREE HIGHGATE, LONDON

20th October 2023 – 29th February 2024

Sri Lankan George Claessen (1909-99) was a self-taught artist and poet whose art was characterised by his mystical outlook and beliefs. As the British Empire crumbled, Claessen’s painting and poetry can be regarded as a headlong flight from the devastating destruction of nationalism and colonialism. ‘Home at last – it must be heaven,’ he wrote as he saw Britain for the first ti me in 1949, glimpsing the rooftops and spires of Gravesend from the ship that had brought him from Bombay. Settling in North London for the rest of his life, those spires seen at the end of a long voyage stayed with him, creating in his art a sense of aspiration and of belonging. He was a founding member of the '43 Group, the first Asian modern art movement established in August 1943 in Colombo. He was a Londoner for his last 50 years.

Dawn Chorus, 1988, woodcut, (detail)

Ken Kiff: A Hundred Suns

AT THREE HIGHGATE, LONDON

2 October 2024 – 5th January 2025

Three poems by Mayakovsky, O’Hara and Ken Kiff’s close friend Martha Kapos shed light on the way Kiff, like Paul Klee before him, took a line for a walk, and then another line, and then yet another. Kapos’ poem was inspired by A true account of Talking to the Sun at Fire Island by Frank O’Hara, which was written in jealous awe after reading Mayakovsky. The three poems here, the three conversations between the three poets and the sun, look for the reason to get out of bed in the morning.

Visiting Hell in a Boat, 1973

MARKO MÄETAMM: UNLEARNING RIGHT FROM WRONG

AT IRAGUI GALERY, PARIS

14th January 2025 – March 8th 2025

Fairy stories are at the heart of this exhibition as they were one of the many ways generation after generation of our ancestors tried to guide their children. The ‘Grimm’ elements of fairy stories were vicious as they were trying to toughen us up, but Mäetamm has taken this to new levels. It is as if he has purloined the wonderfully direct re-drafting of ancient tales by the Anglo-Norwegian writer Roald Dahl and cut out any unnecessary niceties. He is a barometer of the changing understanding of the line between reality and fantasy. In the days when Grimm and even Dahl were writing people were condemned if they were dreamers. In the age of computers, internet and social networks, those living in their heads, can be more aware of the realities of the day than anyone. Yet people persist in mocking those that don’t follow the prescribed single line of accepted thinking.

Henry Ward, Medusa, 200 x 320 cm, mixed media on paper, 2021

Lost in Translation 1, 2, 3: Henry Ward & Mark Wright

at the In and Out Club, London

19 October - 30 November 2021 (by appointment only)

Catalogue available with texts by Jonathan Watkins and Alistair Hicks. An Aleph Contemporary Exhibition.

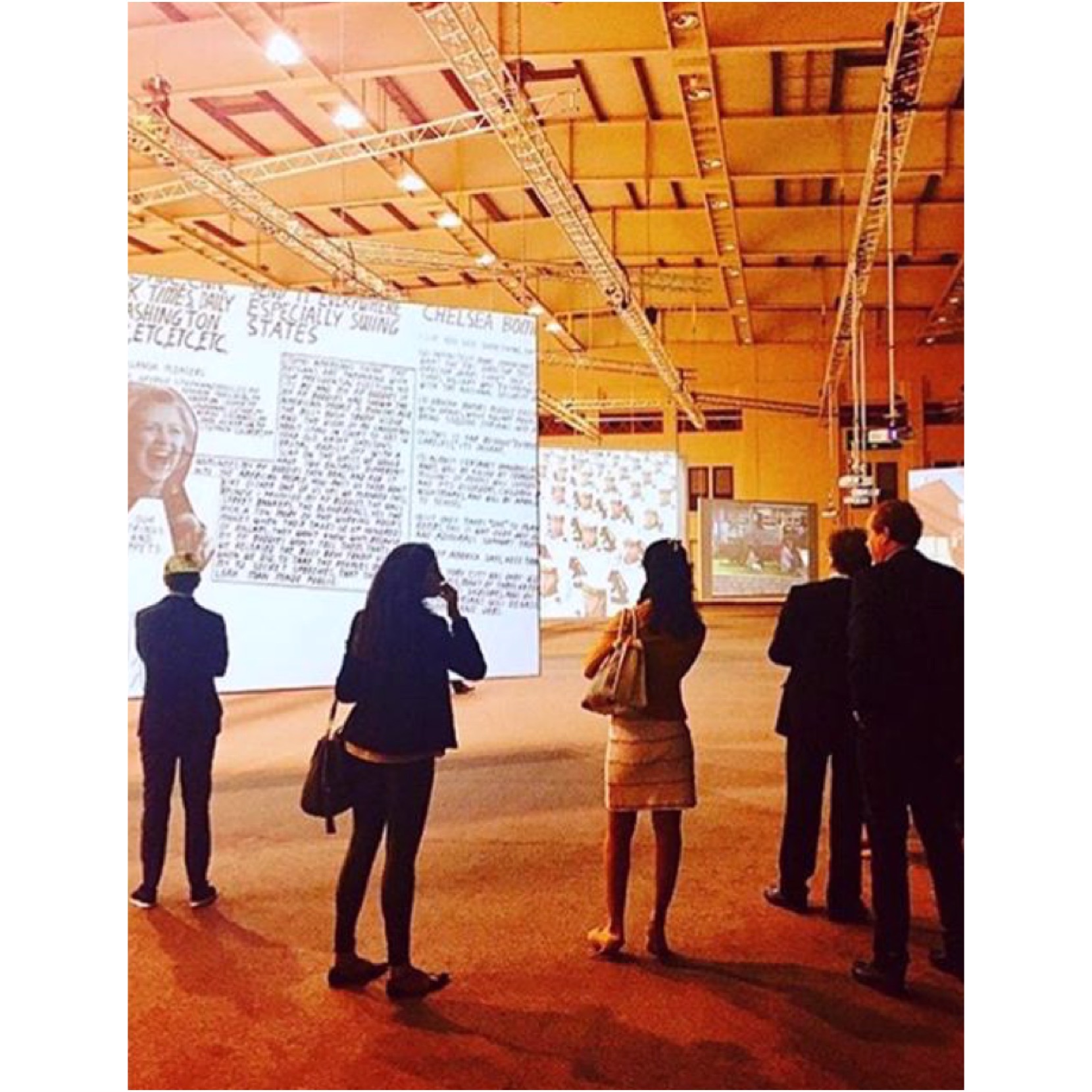

Raqs Media Collective, Re-run 2013, Single screen life-sized video projection; Re-Enactment of Henri Cartier Bresson’s Photograph of a Bank run in Shanghai in 1948. Continuous loop. Installation View MAB Society, Shanghai, 2015.

The Time needs changing

At the Pera Museum, Istanbul

13 December 2018 - 18 March 2019

Time is the enemy of us all: it needs changing. King Canute tried to demonstrate that even the greatest rulers are unable control the relentless tide of events. When he commanded the waves to retreat they rudely disobeyed him. Yet his intended lesson has been ignored by endless emperors, kings, religious leaders and other politicians who have continued to try and manipulate time to keep the rest of us in 'our place'. Recently leaders in Russia, North Korea and indeed Turkey have played with time zones to realign themselves geo-politically. But does time always have to be our enemy? Is it an enemy of the three artists of this show - Cao Fei, Nilbar Güreş and Raqs Media Collective. Time is just one of their many subjects, but all three of them invite us to engage with time, not just as a measure of our fast disappearing time on earth, but as a way of understanding ourselves.

Cao Fei, A Mirage (Cosplayers Series), inkjet print on paper, 75 x 100 cm., 2004

CAO FEI

As well as showing some of RMB city's history, there are some earlier photographs by Cao Fei including COS Players: Mirage, 2004.

Cao Fei, Whose Utopia? - My Future is Not a Dream, photograph, 120 x 150 cm., 2006

Cao Fei, Whose Utopia? - My Future is Not a Dream, photograph, 120 x 150 cm., 2006

NILBAR GURES SKIRTS

Nilbar Gures attack’s masculine time by stitching together her version of an ‘infinite tower’ with bits of skirt.

Nilbar Güreş, Pink & Fur, Pattern & Carpet, Pattern & Necklace, Orange & Earrings, Navy Blue & Messy Hair, Green & Tears, Dark Purple & Pearl, 363 x 75 cm., 2014.

Asli Çavuşoğlu's Place of Stone questions our ideas of modernity. It has just been shown at the New Museum in New York

The Crime of Mr Adolf Loos

At Axel Vervoordt Gallery, Nr. Antwerp

16 March 2019

Adolf Loos' cornerstone essay of Modernism, 1908, Ornament and Crime, hijacked the idea of modernity. 'Unnecessary' decorationwas removed from any work of art with pretensions to modernity. Kamrooz Aram, one of the artists in the show, pointed out that at a drop of a pen Loos dismissed two thirds of the world where ornament has and is an essential part of life. The aim of this show is not only to make people re-examine their prejudice against ornament but rather to show that that the battle is not between ornament and simplicity but how ornament is just as revealing about the way we think and feel as a straight line.

All the artists in the show were selected to demonstrate that Loos' definition of modernity was an unwanted diversion in the pursuit of the new and meaningful.

The Crime of Mr Adolf Loos is co-hosted and supported by Turkey One.

Zheng Guogu has both a series of paintings composed of brand names and chairs that are a cross between Ming and Diego Giacometti

List of Artists: El Anatsui (Ghana), Nikita Alexeev (Russia), Kamrooz Aram (US/Iran), Çakar, Cansu(Turkey), Asli Çavuşoğlu (Turkey), Nilbar Güreş (Turkey),Anish Kapoor (UK), Waqas Khan (Pakistan), Kimsooja (US/Korea), Shozo Shimamoto(Japan), Fahrelnissa Zeid (Turkey), Zheng Guogu (China), Yangjiang Group (China)

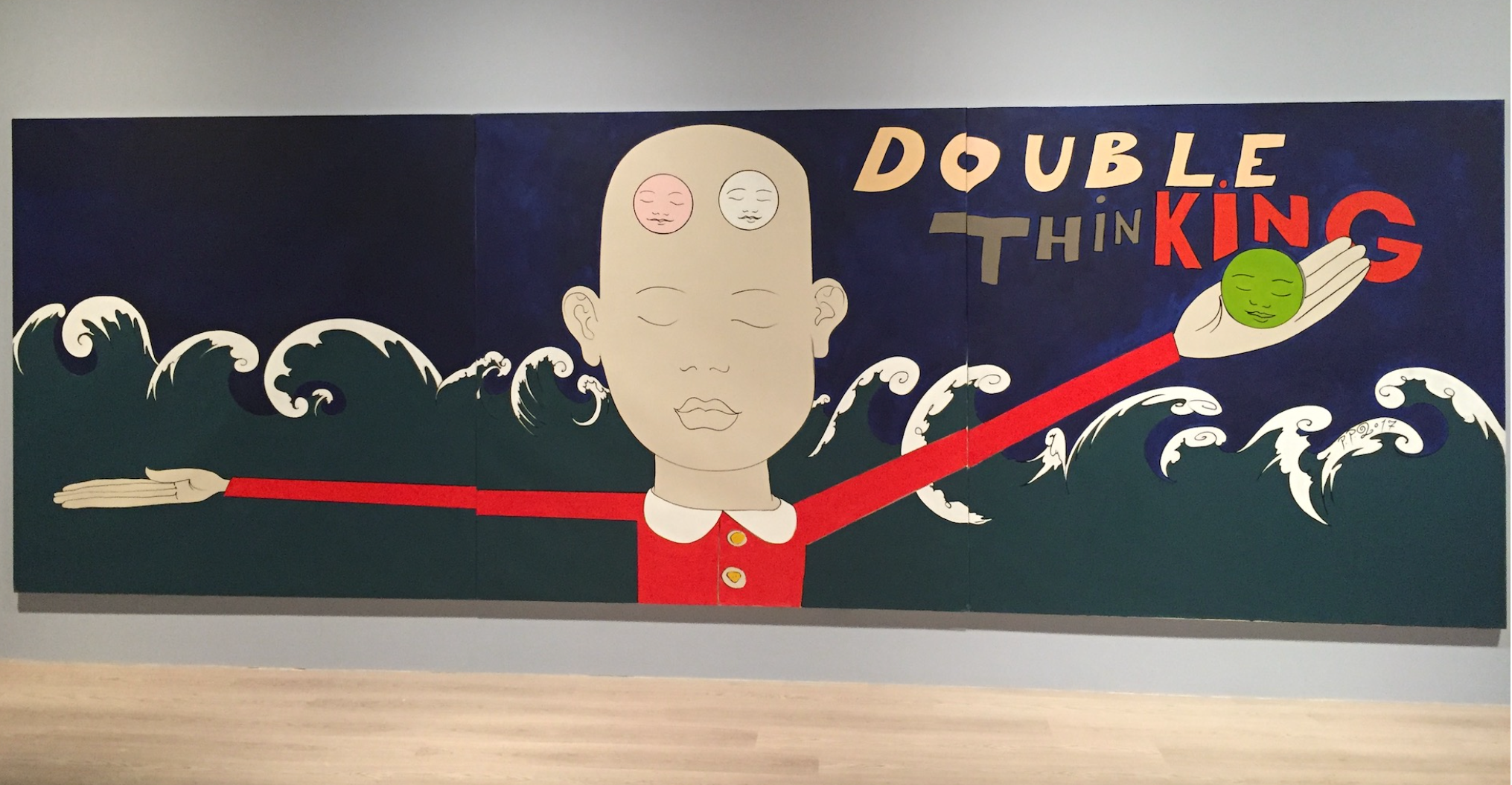

Pavel Pepperstein, who provided the title, also made an eight metre long triptych for the show

Erik Bulatov was perhaps the first to consciously balance words and text, almost as if he was creating the credits for a film

Doublethink: Double-vision

At the Pera Museum, Istanbul

25 May - 6 August 2017

Thinking has changed radically, but many people don't appear to have noticed. Our institutions have been stuck on linear Neo-Platonic tracks for 24 centuries. These antiquated processes of deduction have lost their authority. Legal, educational and constitutional systems rigidly subscribe to these; they are 100% text based. This exhibition uses the work of 32 artists from all round the world to show a new balance in thinking between text and image.

'You probably think of Doublethink as a negative concept. We in Russia think of it as just the beginning,' says Russian artist, Pavel Pepperstein. Pepperstein and other Moscow Conceptualists were not acknowledged as artists by the State in 1970s and 80s, so had to form a new way of communication. They redefined conceptualism, away from the American, European idea of a pure idea, to being a balance between text and image. The refusal to rely just on text or just on image to communicate has in the last thirty years become an essential part of the new doublethinking.

List of Artists: Yuri Albert (Russia), Nikita Alexeev (Russia), Kader Attia (French/Algerian), Sarnath Banerjee (India), Hera Büyüktaşçıyan (Turkey), Erik Bulatov (Russia), Asli Çavuşoğlu (Turkey), Olga Chernysheva (Russia), Marila Dardot (Brazil), Marcel Dzama (Canada), Tracey Emin (UK), Merike Estna (Estonia), Sandra Gamarra (Peru), Claire Fontaine (French), Duan Jianyu (China), Ali Kazma (Turkey), William Kentridge (South Africa), Waqas Khan (Pakistan), Anselm Kiefer (Germany), Galim Madanov (Kazakhstan), Marko Mäetamm (Estonia), Mónica de Miranda (Angola), Ciprian Muresan (Romania), Arkady Nasonov(Russia), Pavel Pepperstein (Russia),Raymond Pettibon (USA), Raqs Media Collective (India), Thomas Ruff (Germany), Nedko Solakov (Bulgaria), Erdem Taşdelen (Turkey/Canada), Gavin Turk (UK), Keith Tyson (UK), Yangjiang Group (China).

Pavel Pepperstein, Fire in Moscow, acrylic on canvas, 151 x 200 cm., 2016

Tragic Timing

Pavel Pepperstein and Marko Mäetamm

Odile Ouizeman Gallery

30 May - 22 July 2017

Neither Pepperstein nor Mäetamm really care whether you weep or bellow with laughter. They live and work on their nerve-ends. Their prime aim is not be funny or tragic, but they are both. We don't see Napoleon weeping as he sees his treasured prize, Moscow, go up in flames. Everyone is not laughing while they have fun in Mäetamm's orgy.

Comedy usually relies on timing, which makes it difficult for artists making lasting paintings. Pepperstein and Mäetamm are two contemporary artists breaking this rule, and part of the reason for their success is that they are not comics. They are not stand up comedians, deliverers of one punch line. They get into our hearts and heads through those tingling nerve ends.

Pepperstein usually operates on a macro, almost cosmic level, while Mäetamm pads through his own home and looks under the beds , sofas and the cracks between the family unit. The aim of this exhibition is to show how these differences actually highlight a common conceptual approach. They both live in their heads and offer to take us with them. They are like separate planets with their own atmospheres and gravitational fields, yet they are in the same galaxy. Mäetamm's Circus is an allegory for all art and all fantasy. He appears to have actually cut his wife in half when it is only meant to be a trick. Did Ivan the Terrible really mean to kill his son? Pepperstein reduces the act to its cartoon simplicity.

Perhaps both Pepperstein's and Mäetamm's work is about timing after all, but it is the very questioning of the man made invention of time. The artists and their audience can happily and amusingly live in their heads most of the time. Then irreversible tragedy strikes.

Marko Mäetamm, Bomb, 2017

Installation view

Floating World

At Art Baab, Bahrain

22 March - 26 March 2017

The world does not normally float in front of us, but over thirty artists from China and Japan to Canada, from Denmark and Estonia to Egypt and Sharjah, made this happen in Bahrain. Challenged with injecting a sense of what is happening around the world into an art fair exhibition hall, Jonathan Watkins came up with the idea of being able to walk around and fleetingly glimpse different perspectives. There was a strong blast of feminism coming from close to home with a work by Ebtisam Abdulaziz (Sharjah) and her autobiography of herself walking around in a body tight suit on which figures from her bank statement was printed. Christina Lucas (Spain) showed a film of dogs getting up walking on their hind legs. It was a belated response through Virgina Woolf in a Room of One's Ownagainst Samuel Johnson's remark 'Sir, a woman’s composing is like a dog’s walking on his hind legs. It is not done well, but you are surprised to find it done at all.' Iv Toshain (Bulgaria) phalanxes of marching women are mesmerising. It is as if we see and hear from their synchronised boot steps the tension in the world, not just between men and women, but the fear of war in places such as North Korea. Cornelia Parker (UK) simply turns her camera on the Trump rallies during his election campaign. There were moments of respite in our Floating World. Artists danced. Gillian Wearing (UK) just going out in the shopping mall and Dancing in Peckhamand Merike Estna (Estonia), showing her life-long love affair with painting by actually dancing with a canvas. Marcel Dzama (Canada/USA) caught a quiet moment in his dancing team's rehearsals and captures the beat of life itself.

I am considering a diet after FAD magazine's kind words: 'Curatorial heavyweights Jonathan Watkins and Alistair Hicks (Ex-Deutsche Bank Collection) are behind this spectacular video installation comprising of 32 huge screens which form the backdrop to the fair. The videos feature documentary footage and work from some of the most important international artists today. Like a forest of moving imagery, the ‘Floating World’ installation features large scale suspended projections – 6 meters wide.'

Artists of the Floating World:

Ebtisam Abdulaziz (Sharjah), Fiona Banner (UK) , Cao Fei (China), Alice Cattaneo (Italy), Neha Chosky (India/USA), Marcel Dzama (Canada), Merike Estna (Estonia), Michel Francois (Belgium), Graham Gussin (UK), Nilbar Güreş (Turkey), Luts and Guggisberg (Switzerland),Flo Kasearu (Estonia), Dean Kelland (UK), Othman Khunji (Bahrain), Sofia Hultén (Sweden/Germany) Cristina Lucas (Spain), Maha Maamoun (Egypt), Marko Mäetamm (Estonia), Adrian Paci (Albania), Cornelia Parker (UK), Raqs (India), Noguchi Rika (Japan), Shi Jong (China), Shimabuku (Japan), John Smith (UK), John Stezaker (UK), Beat Streuli (Switzerland), Evren Tekinoktay (Denmark/Turkey),Jan Toomik (Estonia), Iv Toshain (Bulgaria), Gillian Wearing (UK), Ming Wong (Singapore/Germany)

Installation view

Landscapes in three languages - Nikita Alexeev

Narrative Projects, London

17 September - 31 October 2015

Nikita Alexeev showed three series in this exhibition and made a video of a performance.For the perfomance he made eighty drawings on grey warm paper. He fly-postered them around London. They bore the legend ‘That’s true in tongues.’ This references Wittgenstein and of course the Biblical first word, the Logos, but just as important is the way the drawings balance text and image.

In the catalogue Alexeev wrote stories about each of three series of paintings and I annotated the stories. Here is one:

Disappearing Landscapes

Long time ago, as many others, I studied photography. I tried to capture things happening around me with my eyes and an artificial eye in the form of a lens. I photographed mostly landscapes because they are less changeable than people, animals or even 'nature morte' (though, perhaps, it is to the contrary: there is nothing more ephemeral than a landscape). But now I realize that I was fascinated more by the dark closet, barely lit with the red lamp, and by way that the image was gradually emerging from the darkness on the photo paper put into the developing solution, than by the shooting itself or by viewing the ready photos. I gave up photography long time ago, partly because with the advent of the digital era the magic of the dark room (camera obscura) and related almost alchemical rituals had disappeared. Moreover, I am now more into the phenomenon of disappearance than into appearance / development. That purely optical state pushes you to serious reflections when you see that all is fading away, colours are being replaced by more light and finally there will be only light. Or to the contrary, only darkness.[i]

[1]Nikita Alexeev starts as if he is relating an anecdote, but a little story builds up as if it is emerging from the dark room. It can be read as a small debate extolling painting above photography, but face value is never going to interest Nikita for long. When he says he preferred landscapes as they were less changeable than people, I think of the British painter Frank Auerbach and his early desperation to pin life down, to find the permanent in the ever-changing world around him without losing the spontaneity. The workaholic Auerbach often takes over fifty sessions to finish a painting, but after each session scrapes off the paint to start again. The desire to keep it fresh makes him just build on memories. Alexeev is building his text as a painter, but paradoxically this little story reveals more about him as a painter than as a writer. His painting in words evokes the Turkish Nobel Prize winner, Orhan Pamuk, who thinks of novelists as painters. In‘The Naive and the Sentimental Novelist, (Faber and Faber, London, 2010), Pamuk wrote‘ novels are essentially visual literary fictions... As I prepare to transform my thoughts into words, I strive to visualise each scene like a film sequence, and sentence like a painting.’ As Auerbach has discovered the canvas can only contain so much paint and never enough information. Alexeev does not scrape his old works off, but he has other ways of releasing the tension, of deflating the pretension. He lives in a simple world of tablecloths and landscapes: his landscapes are in many languages and they disappear.

Nikita Alexeev's Disappearing Landscapes literally do disappear in certain lights. Certainty is questioned

Disappearing Landscape, 2015

Raymond Pettibon: Living the American Dream

Part of Home and Away

Kumu, Eesti Kunstimuseum, Tallinn

29 May - 13 September 2015

Raymond Pettibon: an exponent of the American Dream?

Raymond Pettibon’s mother and aunt made their way to America during the Second World War. Raymond’s uncle fought for his country and was rewarded by Stalin with an eleven year stint in a gulag.[i]Raymond was the offspring of a polarised world. As a child he remembers his mother and aunt anxiously talking about his uncle outside his door. It is not surprising that Pettibon draws a divided world. He lets the energy and passion of the American dream spill out, but he confronts the consequences.

One might mistake Pettibon’s starting point as Roy Lichtenstein, but Pettibon’s use of text in his drawings is actually far removed from the All-American teenage comic-style of this Pop star. His balance between image and text is much closer to Russia than his fellow-American’s. He has not consciously been influenced by the Moscow Conceptualists and their critic Boris Groys, who has treated Conceptualism as a search for the balance between the image and the word. Yet Pettibon’s drawings are battlefields between drawing and writing.

The Treachery of Imagesby Magritte provides a better entry point to Pettibon’s work than Lichtenstein, but it is not as one sided as the Surrealist’s title suggests: it is simply that the text and image fight. As with the picture of Magritte’s pipe, the text is not lying, it isn’t a pipe; it is just a picture of a pipe. But why is the image accused of the treachery, when the text is just as treasonable. According to some scientists, as little as seven per cent of our communication comes through words. Words on their own are rarely enough, hence the rash of smileys in our texts. Pettibon’s work is as full of contradictions as life itself, and it rants against these inconsistencies and yet at the same time relishes the extra complications. Without resorting to astrology it is possible to see the poles Raymond was born between still influencing his work - the optimism and seduction of the dream to get away to a ‘land of freedom’ clashing with Realpolitik. This only supplies some of the tension: the more frightening elements in Pettibon’s vision of the world come with the loosening of the old polarities. He is an involved observer and the scream ‘Vavoom’ comes from deep inside him.

[i]Otto Peters spent eleven years in a Soviet prison camp at Norilsk, behind the Urals. He wrote a book about his experience there and in the War, The Boy of Independent Estonia, (details)

Raymond Pettibon, No Title (Without their ears...), 2010

Raymond Pettibon, No Title (The world is), 1995

It is easy to be distracted in a Pettibon exhibition by the sheer weight of tangential information, the amusing asides and the damning verdicts. The aim of this exhibition is to try and show the simplicity and power of this Estonian American artist, by isolating a few of his main series, and then let the confusion creep back in with some work he is making specially for Estonia.

Pettibon’s American dream is populated by surfers and baseball players. Another recurring theme is the travel machine that unleashed the pioneering spirit upon the vast land mass that now makes up the United States of America – the train. These three series (baseball, surfing and trains) form the backbone of Pettibon’s work. Subversion creeps into even these most positive images of American culture at its swashbuckling best.

Pettibon is a pen-name given inadvertently to Raymond by his father,R.C.K. Ginn, who affectionately referred to his fourth and penultimate son as ‘Petit bon’ (my good little one). His father was an English teacher who wrote spy novels, so it is perhaps not surprising that many of Raymond’s works trigger literary references. He treats baseball much as Philip Roth does in The Great American Novel.’ The instant hit is of the healthy nation at one with itself and its place in the world. Just as there is the expectation of a home run in the muscle and sinew of Pettibon’s players, the title and initial tone of Roth’s novel is upbeat, but the world unravels as the Patriot League is ripped apart by McCarthyism. There is a passage at the end of the book in which the hero tries in vain to defend himself from the trumped-up courts’ accusation of Communism. It reads like a Pettibon text: ‘This Committee and its investigation is a farce. I refuse to be a party to it. I refuse to answer any more of your questions, particularly questions about my associations, past, present, or in the life to come. I refuse to answer any questions having to do with my political beliefs, my health habits, my sex habits, my eating habits, and my good habits, such as they are.... I refuse to participate in this lunatic comedy in which American baseball players who could not locate Russia on a map of the world – who could not locate the worldon a map of the world – denounce themselves and their teammates as Communist spies out of fear and intimidation and howling ignorance ...’[i]It could almost be Pettibon speaking, yet his own use of language is not that of a novelist. Though he plays with words, though they bite, they are never completely an end in themselves: his words work in partnership with images.

Pettibon’s trains are usually from the steam days of the settlers. Many movies, many myths celebrate the drive West, the quest ever westwards to new horizons usually in wagon trains. In reality it was the trains that transformed the country and they were built in a relatively short time. Congress only passed the Pacific Railway Act in 1862. The first track across the nation was completed within seven years. There was an element of East meets West. Of the 4000 workers on the track in the last months, two thirds of them were Chinese. Cynics will rightly point out that market forces played their part in that not only did the Chinese have the necessary skills with explosives, but they and their bosses were prepared to take greater risks with their lives, yet there was a uniting dream. On May 10th1869, Chinese and Irish crews laid the last ten miles of the two railroads coming from the East and West and meeting at Promontory, Utah. They managed it in twelve hours.

Young Raymond Ginn went West. He was broughtup in Hermosa Beach, California, and he would head as far west as he could into the sea and the surf. Written in capitals along the bottom of one of his surf drawings is the instruction ‘And stand up tall! Straight.’ There is a worship of the wall at the end of the journey. Another work from this series shows a man enveloped by a wave. The words at the bottom read: ‘The bright flatness of the California landscape needs a dark vaulted interior.’ The mood changes and in one 2004 work we see an even more diminutive figure in danger of being swallowed by a succession of mountainous waves. The waves are coming from the East. It is difficult not to think of that most famous tsunami of all, The Great Wave of Kanagawa, as printed in a woodblock by Hokusai around 1831.

Repeatedly Pettibon reminds us that there is too much information out there for one little mind. Kanagawa overlooks the same Pacific Ocean stared at by the young Raymond. Hokusai was painting just a generation before the Chinese labourers came to work on the early trains in the 1860s. America was racked at the time by the Civil War, but let us not forget that Europe was changing rapidly at the same time. The first train went across America before Germany and Italy emerged fully as nation states. Hokusai’s and Pettibon’s waves have brought much destruction with them. Some of them can be temporarily conquered, but there is always a threat of an even bigger wave.

It is not only Pettibon’s water walls that bring a fear of dissolution. A mixed cluster of Pettibon’s work can make it seem as if the world is dissolving around us. The Vavoomseries is the primeval response to this. While the American dream encourages the individual to think that anything is possible, Vavoomis the complaint against individual inadequacies, the total failure for the single figure to cope with his surroundings. It is a full stop as emphatic as Munch’s Scream. The scream is not enough. Men and women see the world tumbling around them as Pettibon does and know that their protest is not enough. How do you look at a Pettibon? Do you read the text first? I doubt it. There is not the same urgency as in a comic or a Lichtenstein to read the words. It is usually only as one looks at the work more carefully that the meaning with all its barbs comes out.

There are countless different ways of looking at Pettibon. Andreas Trossek, in his article ‘Raymond Pettibon, America, Estonia ‘ in Kunst.ee,[ii]reveals that it was Goothat first cemented his relationship with the artist. Goo was the eighth album of Sonic Youth, Raymond’s brother Greg’s punk band. Raymond designed the cover and launched his career as an artist. Music, like literature, is another key to Pettibon’s work.

The historical part of the show is merely an introduction, which is why we have kept it simple and powerful. There is already tension in the show between the obviously American subjects and the serried ranks of Stalin, which are a testament to Pettibon’s uncle, Otto Peters, in surviving Stalin. When Pettibon came to Tallinn for this show it was only his second visit. The overriding subject of his work is about America and its relationship with the world.

[i]Roth, Philip, The Great American Novel, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York, 1973 (quote taken from Roth Philip, Penguin Books, New York, 1981, p371)

[ii]Trossek, Andreas, ‘Raymond Pettibon, America, Estonia,’ Kunst.ee, Tallinn, Feb 1, 2011, http://ajakirikunst.ee/?c=magazine&l=en&t=raymond-pettibon-america-estonia&id=383. Ultimately it was this article that led to this exhibition. I had no idea that Pettibon was Estonian when I showed his work to Rein Lang, then Minister of Culture of Estonia, at Frieze New York. Fortunately Olga Temnikova had read Trossek’s article and was around to illuminate us. We soon discovered from Sadie Coles and Shaun Regen that Raymond had never been to Estonia, I suggested it was high time he had a show here.

Marko Mäetamm: Feel at Home

Part of Home and Away

Kumu, Eesti Kunstimuseum, Tallinn

29 May - 13 September 2015

Feeling at Home

Even more basic than the American Dream is the desire for a home. Don’t we all deserve a home? The search for it can lead us on as long and winding a path as chasing the rainbow over the horizon. I lived in nineteen different places by the time I was nineteen: I certainly did not believe all the cold dormitories were home. This introduction to Marko Mäetamm’s exhibition can neither rely solely on fact nor resort to pure fiction. Though I am half-English, I know the home is not usually a castle. Home has to be more than hard bricks and mortar; it is mostly in the head, but that is not enough. It is where the heart is, but finding out about that can be a long and hard journey. Mäetamm takes us on this journey.

Marko keeps us waiting in a purgatorial space - the hall. After a time the realisation comes that the artist is not going to come in person to be our personal escort. He does not need to. His art is so personal that it triggers screaming nerves in all of us. It is almost impossible not to identify with his characters and stories. They come from his home: they come from our home. Like a very adroit playwright he has suspended belief so successfully that he makes his audience do much of the world in building up the characters. He gives us hints, he helps us, but this is a performance, a collaboration between him and us. Like Pettibon, he refuses to rely solely on images or solely on text.

In that half way no-man’s land, otherwise known as a hall, the artist employs a third presence. His art seems to flutter from his shoulder and lead us visitors into this strange building where fiction is interchangeable with reality. The warning signs are clear for all those who have ever seen a horror movie. Above the chimney is no normal stag or elk’s head, but rather Marko’s torso, with antlers springing from it.

There is a television in the corner. It is playing a film about a hunter. It is a horror story. There is a man in a duck shooting hat. He is stalking. He is inside. He could be in the same house. While we wait in the vestibule, the hunting Sherlock is pointing his gun around the corner of a living room. It is the father of the house. He spies his children. They run and hide behind the sofa. He sees his wife. She scuttles behind the same sofa. Father Sherlock walks heavily towards them, takes out an axe and disappears in the crowded space behind the sofa. His arm rises above the sofa-line. The axe-head is bloody. It rises again. His hand, his arm and the axe drip blood. This is a cartoon story. The figures were only flat cut-outs, and after a short interval the family rise up from the dead, and exit like crabs from their own murder scene.

The artist creates an aura of expectation. He makes us imagine things even worse that we see. Something is flying around our heads: it spurs us on to explore this cavern-like hall. The owners have put a carpet on a back wall. You can take this literally as a sign of orientation or disorientation.[i]Not only has the floor moved ninety degrees to the wall, but there are pictures on the carpet. Even the carpets are competing to tell stories. There is a common expression that ‘walls have ears’ but this is more a case of the walls getting revenge. It is as if they have listened long enough through years of oppression and are now out to talk, to spew out their stories – to tell all.

The walls have bird voices. This is a haunted house. It is difficult for us tour-fodder to stay still. There is a door, so naturally, being brought up on Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland,[ii]we go through it. Before we even fully realise we are in the kitchen, we see the dead body. This is not a cardboard cut out. A life size figure has his head in an old-style oven. It gives the shock of seeing a dead body but actually the crawling knees are still bent. He is in the act of killing himself: he is not dead yet. It is a sculpture so time has stopped, so we can’t save him. The logic of the story indicates that the hunting father cannot face himself after killing the rest of his family, but that seems too easy an explanation. He is dressed casually, and seems far removed from the hunter. The whole situation appears to have switched. He appears to be the hunted rather than the haunted till we examine the blue and white tiles on the oven back. They tell a completely different story, a more equally matched one. There is yet another television in this kitchen: every room seems to have a television. The unseen presence turns it on. It is playing a blue film. It is the same story that the tiles are telling. The Portuguese tiles are simply the stills from the animated film, Blue Story, 2010.

The house gives us clues as to how it might fit together, but it doesn’t. It is like an MC Escher jigsaw puzzle. The family movie is set in the living room, reminiscent if not the same as the one seen in the film in the hall. The sofa that hid the foul deed could be a recycled version. Two people are sat on the sofa together. They are obviously husband and wife. It is a typical scene of domestic life, except that both have paper bags on their heads. The conversation drifts through the door:

‘It is ok this way,’ the wife was saying. ‘To be honest I was getting tired of seeing your face nearly every day for twenty years.’

‘Same here,’ replied the husband, perhaps rather more forcefully than was necessary.

[i]Though throughout the world there has been a tradition of putting textiles on walls, carpets tends to come from the East – the East and our literal sense of orientation.

[ii]Carroll, Lewis, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, London, 1865

Marko Mäetamm, Marriage, 2015

The stories change. Again they slip like Escher’s images. So many things are connected but may not as directly as one first things. There is more than one story about a hunter. There is more than one hunter. One film connects closer to the story-board printed on the blue-and-white tiles over the oven. Yet there are always changes. There is a picture at the back of the drawing room. The picture shows a couple sitting at a sofa. They aren’t the same. The moving picture of the ancestors has heads showing clearly and freely visible, but the couple depicted on the oven tiles have bags on their heads. In the little picture behind them, their ancestors have bags on their heads. The silence is broken. If one peers too hard beware the legs of Marko the suicide sculptor might trip you up. The television is blaring out an advertisement. It is showing Marko in a bathing suit on Miami Beach.

‘I am Marko Maëtaam! Watercolours, sculptures ... come buy my pictures.’

He was putting his head in the oven and advertising at the same time. The kitchen was too hot for the third presence. It wants to fly next door but is halted by the voices from the next room:

‘Snap their heads off first!’

‘It works.’

‘Of course it works.’

It was a whispery sinister conversation with a whirring of a wings and a slight buzzing. One of the voices might have been stolen from Tony Oursler’s talking street lights which were first shown in Münster in 1995.[i]The lamp talked like a dirty old man. It took advantage of the night time law that one often feels most vulnerable in the pool of illumination.

‘You – you - you, I am going to eat you all?’

We decided we had to go in to break up this party. Surely it wasn’t the husband and wife talking on the sofa?

When is the visitor going to be allowed to see that much promised front parlour scene of husband and wife sitting side by side, whispering through the bags, but the guide is still not taking us to the drawing room. We are in the dining room, which is dominated by a big screen filled with a flight path of hornets. It is the hornets that are talking. The film is entitled La Grande Bouffe![ii] On looking more carefully, the hornets are flying down as if landing on a runway made of ants. The hornets are eating the ants. The overheard conversation was of gourmand, gluttonous large wasps overindulging themselves on an endless supply of insect food. I had always thought hornets fed on dead things. We hover to watch a hornet feast. The anxiety about the tone of the voices had not been misplaced: We are witnessing a massacre.

The funny hornet dialogue should not mislead the visitor. This place is as much about our anxieties, phobias and aspirations as the artist’s himself. The cartoon like figures die and come to life again, but it is not just them. Sometimes the father/hunter figure is Marko: at other times he looks very different. There is a man with wild blond hair and another with scarecrow black. The characters are not only metamorphosing in the art. They are appealing to different sides of their audience.

So far, I as the visitor to Marko’s home, have been playing a role – that of a British interloping curator. So far the references have come from my safe English background – English children’s stories and literature. I am not ready to abandon them yet. I try to break out and tell Marko that this plethora of rooms occupied by different people reminds me of Ilya Kabakov’s Ten Characters, 1970s, but the bid for escape does not work. He does not respond. Marko is playing at least ten characters, and I am not alone either. There are many other visitors being led by a guide, who appeared to be a bird.

The logical end of Marko’s journey would be the traditional heart of the home, the ‘living room, but just as with the search for the American Dream in Raymond Pettibon’s work, the horizon is forever moving. Domestic bliss, as represented by a happy couple on a sofa, always seems to be beyond us, like a carrot a stick. The expectation for the sitting room works both ways: the dream could be a nightmare. The drawing room could be like Orwell’s Room 101[iii]. Though reason tells us that Plato’s and Socrates’ vision of love is the last piece of Greek thinking that has not been exploded, our worst fear is that love is fake, an illusion. Perhaps we need to put paper bags on our heads. Instead we discover another horror at the heart of the house. Opposite the sofa is a piece of furniture, a type of commode, but it has a funnel coming out of the top. The commode is a miniature prison. It has a funnel coming out of the top: it is for pouring food and water to the prisoner inside.

Most normal people would shrink away from such an obvious instrument of torture, but my sick mind immediately clings to a moment of inspiration in English children’s literature. The Oxford don and author, C.S. Lewis, is meant to have had a sadomasochistic relationship with his landlady, Mrs Moore. She was luckily in the habit of locking him in cupboards, where of course while working his way thrv ough the land of his lady’s fur coats he discovered Narnia. My thoughts too often run in circles, so while examining the funnel, I do not follow Lewis’s quest in the Lion, Witch and the Wardrobe[iv]to break the spell of the Ice Queen (aka Mrs Moore), but instead start wondering about who is inside the commode. My hot tip for the prisoner inside, finding his own inspiration in the claustrophobic dark, is the artist himself, but I have no proof and I am just telling tales in a manner that most of C.S. Lewis’ biographers have disdained.

Are we ever going to make it to the bedroom? The answer is probably no. Testosterone and sex bounce around the rest of the house, but another television stops us, or is it a watercolour? The memories of this haunted place fuse. How warped can a mind get that it can confuse a watercolour with a flickering screen? In this film/watercolour the artist is in the bedroom, but he has been waiting for his beloved wife, for he believes it is one of those nights. He waits in bed, but she does not come. He waits: she does not come. He comes back to the living room to retrieve her and she is watching a Jean-Claude Van Damme movie. He asks whether she is coming to bed. She grunts, but not in the right way. Jean-Claude Van Damme is preferred to our hero.

Trying to forget sex, or the lack of it, we stumble towards the garden. We distinctly hear wings flapping with a moment of freedom. There was a glimpse through one of the windows a garden shed, man’s last refuge. The blue movie, Blue Stories, 2010, had only really turned out to be another family murder story. We needed air. In the garden there is a full size screen. It shows a pond. The artist and his wife are sitting on a bench next to the water talking about life. He is asking philosophical questioning, but she is not interested. She will do the ironing or anything to avoid the repetitive line of questioning, or perhaps she wants to go back to her action man, Van Damme.

The shed is the last hope to find the gold the rainbow promises in our backyard, the dream of domestic bliss, or rather the refuge from that so-demanding dream. We hesitate as our guide seems to have abandoned us, flown away. That most English of novels, Stella Gibbons’ Cold Comfort Farm,[v]is warning me that I am not going to find what I am looking for in the shed. The dominating grandma figure of Cold Comfort Farm rules the roost by constantly reminding everyone that her life has been ruined by seeing ‘something nasty’ in the woodshed.

No one wants to be the first to go into the shed, and we were right to be hesitant, as when we enter man’s secret den, the hunch that it was Marko in the commode looks good. A bird cage is hanging from a rafter. It used to belong to Rosetta, the family parrot, who has flown to the freedom of the skies, but now it houses a crouched, squashed and put-upon artist. The dead end of this story ends with a tamed and captive man.

[i]Tony Oursler’s Street Light, 1995 was first shown inSculpture Projects Münster, Germany, in 1995.

[ii]The Grande Bouffe and Blow-Out is a 1973 French–Italian film directed by Marco Ferreri.

[iii]Room 101 appears in 1984 by George Orwell

[iv]Lewis, C.S, The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe,Geoffrey Bles, London, 1950.

[v]Gibbons, Stella, Cold Comfort Farm, Longmans, London, 1932

Marko Mäetamm, How I became an artist, 2006

Subway Station, Monte S. Angelo, Naples

'In the proximity of Mount Vesuvius and Dante's mythical entrance to the Inferno, I found it important to try and deal with what it really means to go underground. The idea was to turn the tunnel inside out like a sock.' Anish Kapoor

Anish Kapoor

Place: No place,

RIBA, Eesti Kunstimuseum, Tallinn

15 October - 19 October 2008

Curated by Rob Wilson and Alistair Hicks

Exhibition co-ordinator: Sophie Walker

Although it only showed his models, this exhibition gave the best view of Anish Kapoor's ambition. It included 45 architectural models of his largest projects. It showed just how important scale is to the artist. The magical and spiritual dimensions of his sculpture are often tied to a sense of awe that one gets from walking around them. We are forced when looking at the scaled down works, the models, to focus on Kapoor's devices, his plans to transport us to other planes.

Temenos, 2006

A 1000 metre long installation at Middlehaven, Middlesborough. Collaboration between Anish Kapoor and Cecil Balmond, Arup AGU

Sometimes the Dress is Worth More Money than the Money, 2001, by Tracey Emin

Beyond Sensation

Art of the Last Ten Years

Jersey Museum and Art Gallery

3 May - 22 July 2007

Guernsey Museum and Art Gallery

2nd September - 31st October 2007

Taking its starting point as the 1997 Royal Academy Sensationexhibition, this smaller exhibition included work by many of the artists that surrounded Damien Hirst in that show including Mat Collishaw, Tracey Emin, Gary Hume, Marc Quinn, Simon Patterson, Gavin Turk and Rachel Whiteread. There were two Jersey connections. There was work by Hirst himself and Jason Martin. Martin was born in Jersey. Hirst was conceived there.

As the title suggests the show was trying to demonstrate that there was life beyond the Young British Artists as well, so a wide range of artists such as Charles Avery, Susan Derges, Moyna Flanaghan and Mathilde Rosier were included. Cornelia Parker was responsible for part of the title of the show as her with her work Beyond Belief.

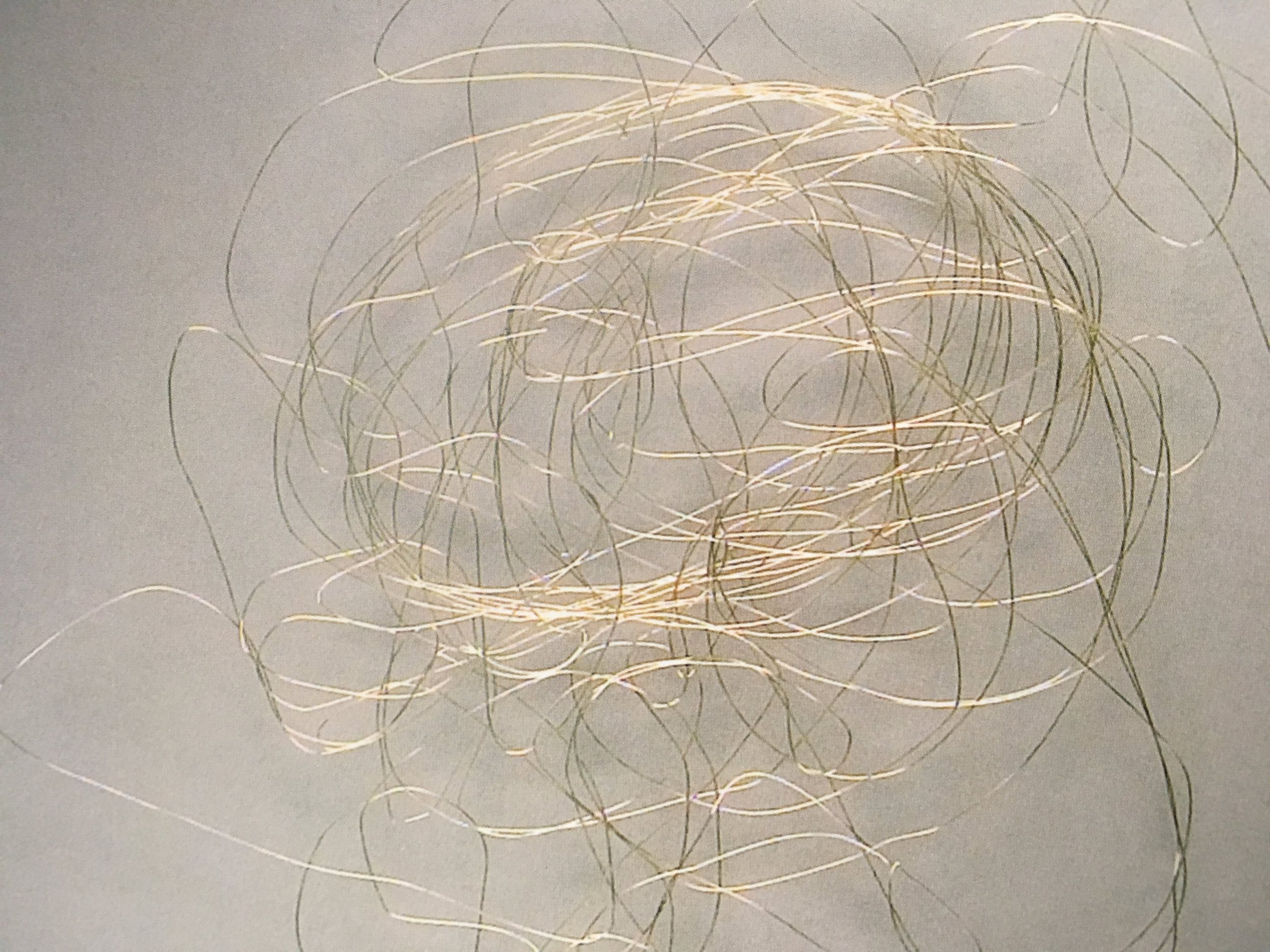

Cornelia Parker melted down a gold cross and made a gold wire drawing called Beyond Belief, 2005

Beuys to Hirst

art works at Deutsche Bank

The Dean Gallery, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art

7 November 2001 - 13 January 2002

Curated by Richard Calvocoressi, Keith Hartley, Alistair Hicks and Friedhelm Hütte

Richard Hamilton, 'I'm Dreaming of a Black Christmas' Collotype and screenprint, 1971. The Bank also owns the White Christmas version too

Concentrating on the natural strength of the Deutsche Bank's Collection in German art from the sixties to eighties (Beuys, Baselitz and Polke) and younger British artists of Hirst's generation. The show was not a straight march from Beuys to Hirst. It also celebrated the holdings of the Bank in Pop art. Deutsche Bank had just opened new offices in Edinburgh and had celebrated by naming conference rooms after Scottish artists so there was an emphasis on young Scottish art. Though the Bank's large Hirst spot painting was too big to get into the gallery safely, Tony Cragg's Secretions, 1998, were dismantled from the London reception and shipped up. The event was recorded by the Scottish photographer, Jeremy Sutton-Hibbert.

Some of Jeremy Sutton-Hibbert's photographs of the opening of the show are now owned by the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art